The Octopus Overlooked the Office

The octopus thrives because it has no shell. Eight arms with distributed intelligence, constantly sensing and adapting to its environment. Contrast this with the hermit crab—dragging around borrowed armor, vulnerable during transitions, wasting energy hauling yesterday's protection.

Most organizations trying to transform themselves face a similar problem. They read about agility, promote cultural change, and restructure for speed. All while operating from fixed, rigid infrastructure designed for an era when work meant assigned cubicles, recurring status meetings, and physical signatures.

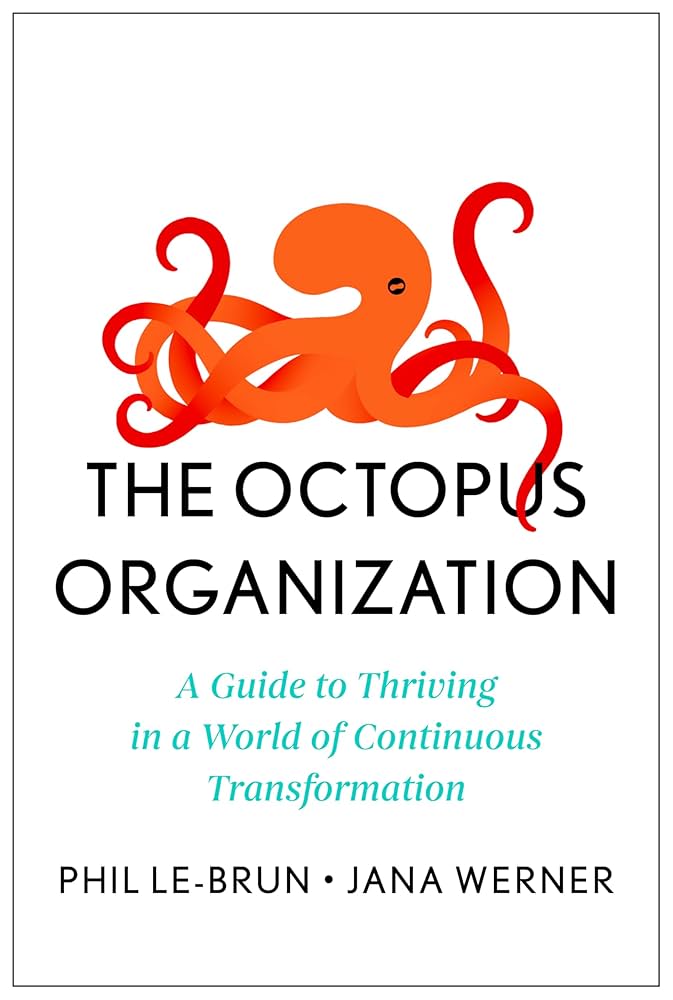

AWS executives Jana Werner and Phil Le-Brun understand this tension. Their book "The Octopus Organization" provides an excellent framework for organizational transformation. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure with thirty-six antipatterns across three categories—clarity, ownership, curiosity—showing leaders exactly what holds them back.

In contrast to the nimble octopus, they liken rigid organizations to Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz.

The book champions distributed intelligence over command-and-control, continuous adaptation over rigid planning, and customer obsession over internal optimization. It’s practical and engaging; I highly recommend it to anyone who thinks about organizational resilience.

But here's what struck me: For a book about adaptability and distributed intelligence, there's a remarkable absence of discussion about the built environment.

Lead Across the Lines of Modern Work with Phil Kirschner

Over 23,000 professionals follow my insights on LinkedIn. Join them and get my best advice straight to your inbox.

The Infrastructure Gap

There are fleeting comments about meeting rooms, one good observation about physically segregated innovation labs undermining distributed capability, and some generic remarks about the attraction of flexible working. But that's it.

I understand why. Werner and Le-Brun are digital transformation experts building on Amazon’s cloud computing heritage. Their expertise runs deep in software architecture and team dynamics. The office falls outside their primary domain, and it’s a sensitive topic at Amazon.

Yet leaders applying their insights face a reality: office buildings as currently positioned, financed, and operated often function as the rigid shell. The Tin Man requires constant facility management. The octopus flows freely.

Could we design buildings differently? Absolutely. The explosion of coworking spaces shows more flexible models emerging. But overhauling a multi-trillion-dollar industry takes time.

Meanwhile, the physical environment either enables or constrains every antipattern Werner and Le-Brun describe.

8 Legs Lessons for Workplace

The built environment shapes behavior regardless of your role—whether you lead CRE/FM, HR, IT, or business operations. Eight of the antipatterns have direct implications for enabling transformation in the workplace.

Creating Clarity

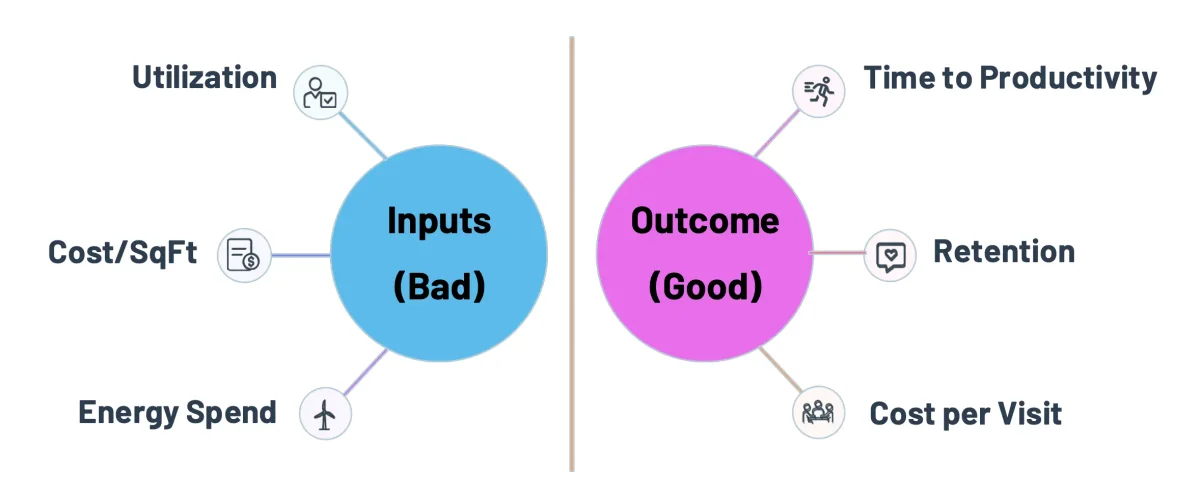

Misusing Metrics (#5). CRE teams obsess over utilization rates and cost per square foot, measuring inputs rather than outcomes. Atlassian broke through by shifting to "cost per visit," measuring value over consumption. When you measure the wrong things, you optimize for the wrong outcomes.

Entrenching Silos (#10). CRE teams and vendors are based on rigid functional identities and partnerships: engineers, transaction managers, designers. Each operates as specialists, struggling to collaborate fluidly. The book describes "territorial taxes" draining organizational energy, and CRE pays this tax internally before creating it externally.

Guarding Information (#11). CRE leaders hold power through market knowledge, acting as gatekeepers for relocations and renovations. This information asymmetry creates dependency. Workplace elasticity terrifies traditional CRE leaders. Loss of control feels like loss of value. We need to shift from Chief Real Estate Officer (control) to Chief Places Officer (enablement).

Increasing Ownership

Creating Dependencies (#17). The book recommends “specialist swarming,” by moving experts into teams when needed. What if we temporarily embedded workplace strategists within business units, so they experience real work patterns, build empathy through observation, and gather authentic feedback? This could better connect space design to genuine needs.

Centralizing-Decentralizing (#18). CRE should adopt a "glocal" framework with minimum viable centralization: booking systems, sustainability standards, safety protocols. Everything else? Local teams decide. Specific offices must serve a clear purpose; implicitly grant freedom to work elsewhere for other needs.

Mismanaging Incentives (#24). The book distinguishes incentives (coercive propositions) from rewards (retrospective recognition). RTO mandates exemplify coercion: "Come to the office or face consequences." The book explicitly says that “Tin Man organizations value presenteeism.” Octopus organizations flip this, e.g., Airbnb offering 90 days of work-from-anywhere annually, which inspires engagement over breeding resentment.

Inciting Curiosity

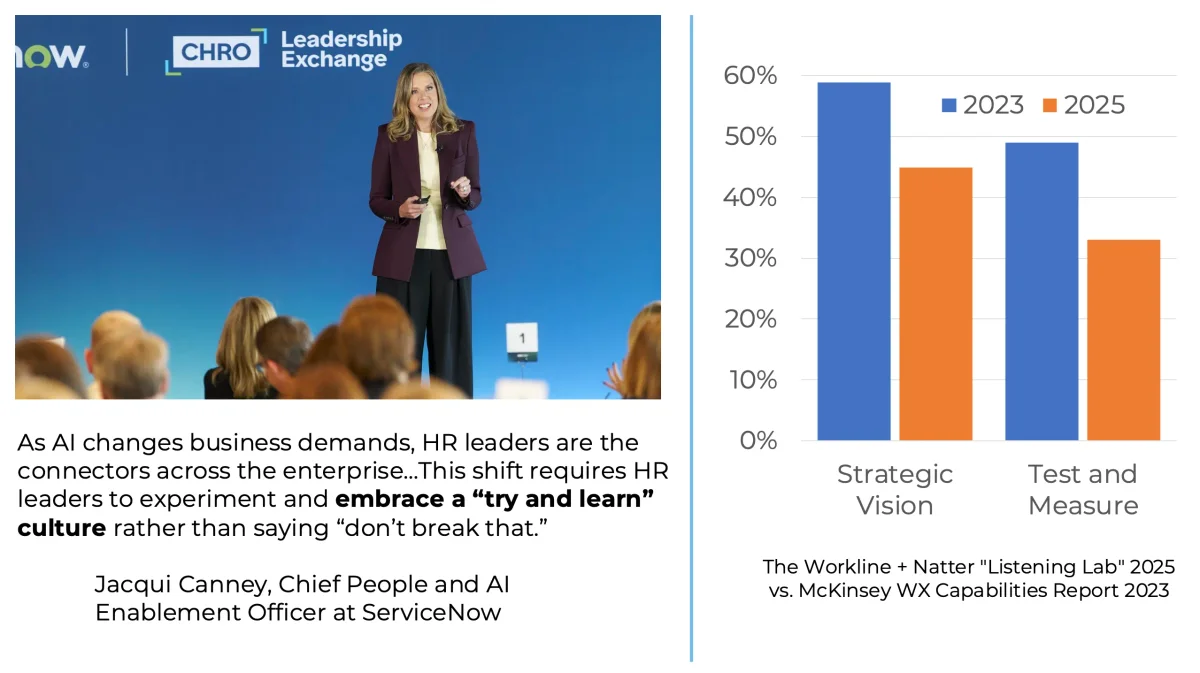

Avoiding Hard Problems (#30). My research revealed a marked decline in CRE experimentation capability. Teams default to polished results rather than tackling hard problems first. An octopus org would start with messy, incomplete progress on what truly matters. Test assumptions quickly. Learn from reality. Iterate based on evidence.

Pretending to Innovate (#36). The authors said that 90% percent of physically segregated innovation labs fail. Innovation theater rather than distributed capability. Declaring an office floor an "innovation center" may undermine octopus strategy. Innovation happens through daily, distributed work across the organization, not in special locations for chosen teams.

Shedding the Real Estate Shell

Here are three ways I believe that real estate leaders in octopus organizations can help build agility and customer centricity:

Embrace opportunity flexibility, not just cost efficiency. Workplace mobility and desk sharing should signal opportunity, not austerity. A culture where people move freely says three things: you're defined by skills rather than your seat, you're encouraged to engage where you add value, and you can move physically and organizationally without friction.

NOTE: I recently posted ten ways to think about desk sharing differently on LinkedIn.

Enable work beyond your walls. CRE leaders often assume spaces they control are best for all uses. The octopus mentality requires releasing that assumption. If a team needs rapid prototyping space, deep focus environment, or client-facing presence you don't provide—direct them to coworking spaces or partner facilities that do. Enablement beats territory protection.

Eat your own dog food through immersive experience. The tech chapter recommends this directly. Embed workplace strategists within business units. Build empathy and document friction points. Gather human-centered feedback about the holistic experience. This also relates to onboarding advice to “let candidates experience team dynamics. Create opportunities for casual interaction through team lunches, coffee chats, or collaborative work sessions.”

The Missing Chapter

The book dedicates an entire chapter (#34) to the downsides of "Segregating Technology." Many tech teams live by jargon like microservices and metrics like uptime, so they are viewed as a cost center. "Shadow IT" is also a problem where teams adopt their own tools.

Multiple other antipatterns address silo problems: working together without team cohesion, hoarding information, gaming budgets across functional boundaries. But no parallel chapter exists for CRE segregation (or HR for that matter), despite similarities.

Many CRE/FM professionals are viewed by business stakeholders as order takers who carry stacking plans, speak in cost per square foot, and invoke lease accounting. The business wants speed, retention, and decision velocity; they don’t (or shouldn’t) care about desk utilization.

The result? “Shadow workplaces,” where teams do real work during offsites in places that better support their collaborative needs than what their office provides.

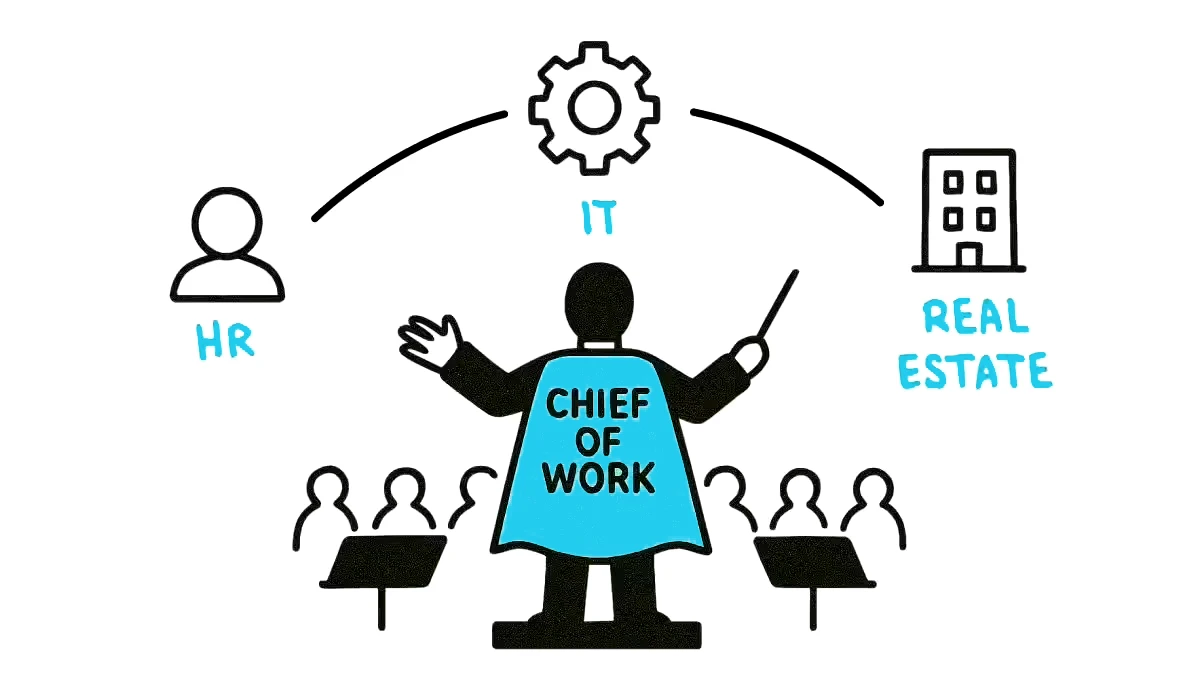

This exemplifies exactly why the Chief Work Officer concept matters. HR, IT, and CRE silos create what the book calls territorial taxes. Energy drains from cross-functional friction. We need unified, outcome-based accountability for how work happens, and how it feels. Single leadership bridging people, technology, and place.

Cross-functional integration will enable the organizational adaptability Werner and Le-Brun champion throughout their book.

What To Do Monday

For Workplace/CRE Leaders:

- Audit your metrics. Shift from measuring utilization to measuring collaboration effectiveness. Track value created rather than cost per square foot.

- Embed and learn. Send workplace strategists to live with business units for a week. Document what enables or constrains their work.

For HR, IT, and Business Leaders:

- Create cross-functional pilots. Assemble business, IT, HR, and CRE partners into single teams with shared success metrics. Learn from integrated structures before scaling.

- Map your territorial taxes. Where do teams waste energy navigating office boundaries? How much friction stems from physical separation, system access, or competing priorities?

For All Leaders:

- Translate to business impact. Ban functional jargon from leadership updates. Practice speaking in speed, retention, innovation velocity, and customer satisfaction.

(You should also read The Octopus Organization, or at least this HBR article from the authors.)

The physical environment operates as either an enabler or constraint. Werner and Le-Brun have written a great transformation map. Now make sure your workplace supports the journey rather than undermining it.

The octopus thrives without a shell. Your organization can too. But first, you have to recognize which rigid structures you're still carrying.