The Doctor Will Share You Now

My last article of 2025 was about students using AI to help doctors triage emergencies. I’m starting this year with a case study about doctors dealing with something less severe, but still very emotional for those involved: sharing desks and offices.

While presenting the Three Horizons at Tradeline a few months ago, I saw a session description so compelling that I contacted the presenter directly.

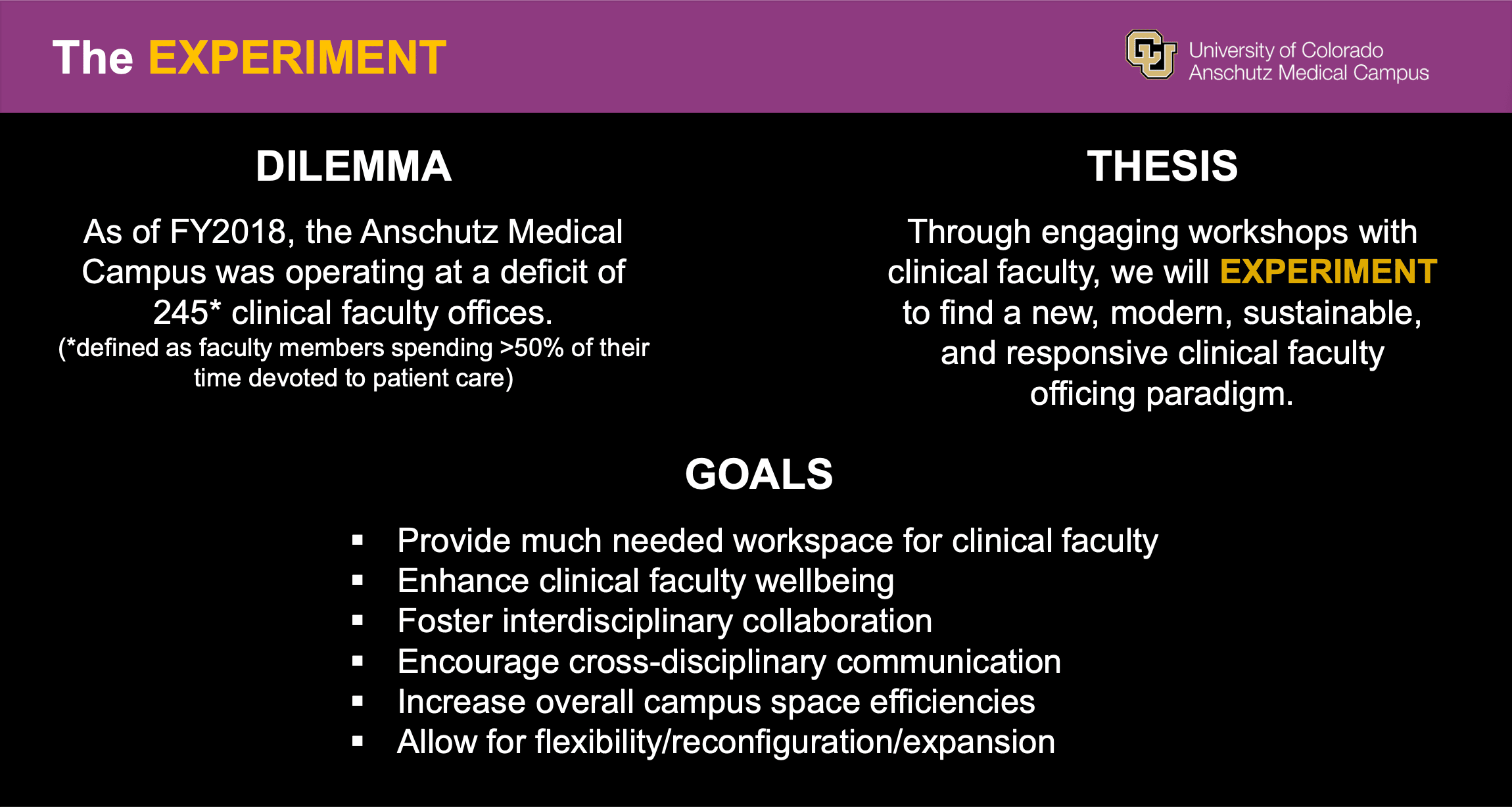

In 2018, the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus faced a familiar real estate problem. They had 245 clinical faculty members entitled to private offices and nowhere to put them. The standard response: millions in capital expenditure for new construction.

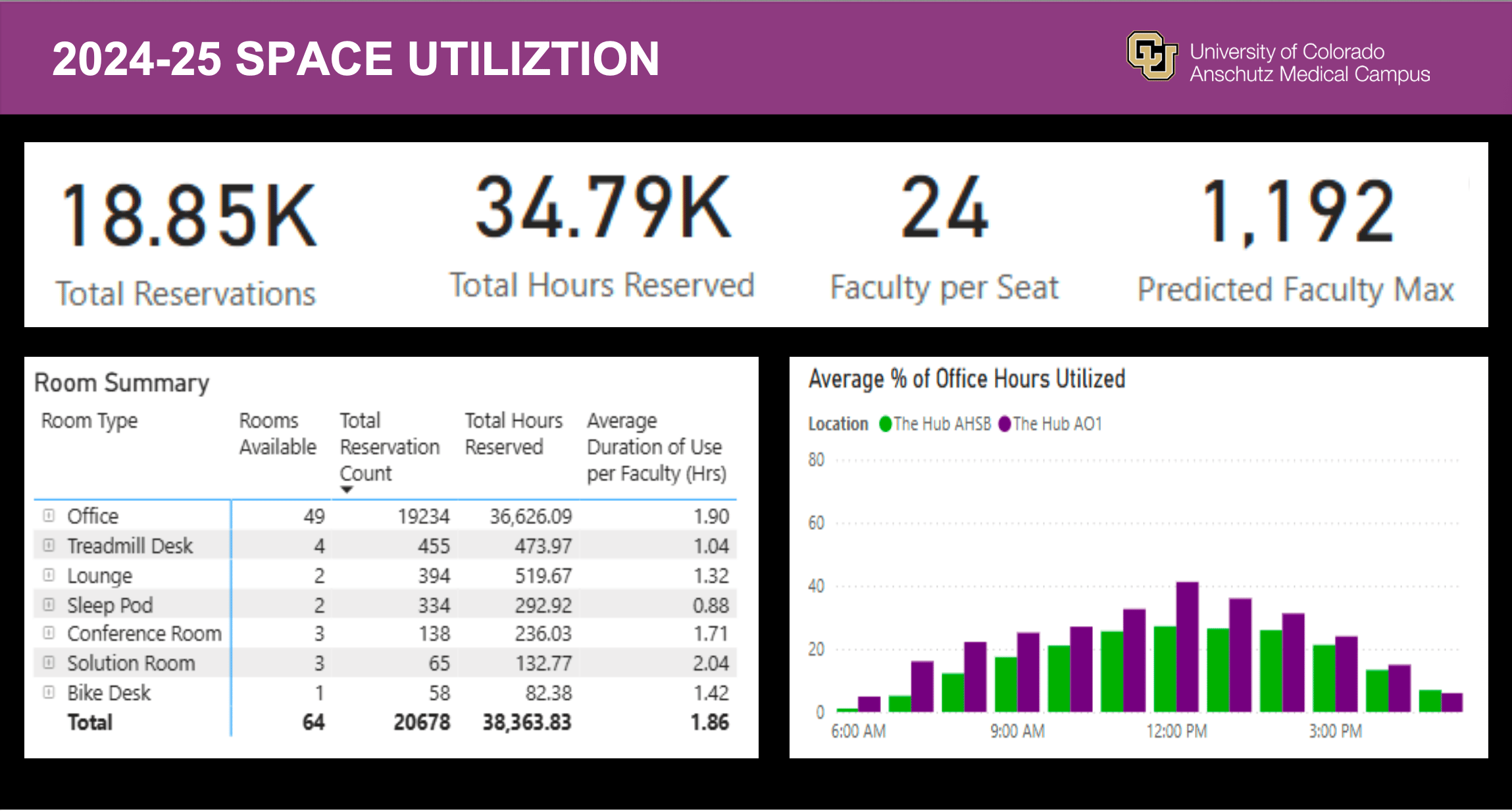

Instead, they built an airport "Red Carpet Club"-inspired pilot called "The Hub.” Six years later, more than 1,000 faculty members had joined the program, and the university avoided nearly $60m in construction costs, $3.5m/year in operating costs, and 156k sqft of new space.

And not a single person has asked for their office back.

The framework that led to this outcome works for any organizational change—AI implementation, team restructuring, or new ways of working. It shows what happens when you treat employee entitlements not as immovable constraints but as experience design challenges worth solving.

Lead Across the Lines of Modern Work with Phil Kirschner

Over 23,000 professionals follow my insights on LinkedIn. Join them and get my best advice straight to your inbox.

Don’t Force It

CU Anschutz made Hub membership voluntary. Faculty could continue requesting private offices if they preferred.

This single decision was the catalyst for change. The new workplace had to be good enough that faculty would choose it over the private offices they were entitled to. No hiding behind mandates or strict policies. Low utilization would signal the product wasn't working. High sustained utilization would validate that they'd solved a problem worth solving.

The voluntary model also created self-selection toward enthusiastic early adopters. When colleagues saw them choosing the Hub over private offices they were entitled to, validation happened organically.

The early response tested that conviction. André Vite, campus architect for CU Anschutz, recalls standing at the open house with barely 20 attendees:

I'm standing there next to the chancellor, and I remember thinking, ‘I wonder if there'll be any sort of severance package when he puts me out on the street.'

Then voluntary adoption started growing.

Service the Solution

The Hub provided shared offices, conference rooms, phone booths, and some perks, including sleep pods, treadmill desks, and showers. But the physical space wasn't the differentiator; the service layer drove the employee experience.

A concierge handles dry cleaning, postage, coat check, meal ordering, and room scheduling. IT support is on-site, solving problems in real-time rather than through ticket queues. There's coffee, snacks, and a monthly newsletter that builds community.

This level of amenity may surprise no one in tech or coworking, but it's quite uncommon in "back of house" offices.

The concierge role evolved beyond what the design team anticipated. They initially imagined only transactional services—picking up packages, booking rooms. What emerged was relationship-based problem-solving. The concierge became "the face of the Hub," the person who makes a complex shared system feel simple.

The pattern extends beyond facilities.

When IT rolls out software, training documents provide the solution—embedded support, and "what's frustrating you?" sessions provide the service. When HR implements performance management, forms and calibration meetings provide the solution—manager coaching on difficult conversations provides the service.

Ongoing service makes employees want to use the solution, regardless of function.

Data Driven Design

The Hub team tracked as many utilization data points as they could, e.g., via badge swipes, reservation patterns, and concierge requests. They also tracked something more complex: satisfaction as a proxy for value, measured by testimonials and voluntary adoption.

The data revealed surprises that triggered changes. Storage went largely unused, so they removed it. Offices without technology were less popular, so they put a standard kit in all of them. Concierge staffing was adjusted without degrading service.

This iterative approach worked because the "experiment" framing gave permission to evolve. Changes signaled learning, not failure.

This capability is rare in real estate functions. My “listening lab” research revealed that most CRE teams struggle to iterate after occupancy because they're measured on delivery—project completion, budget, square footage—rather than whether solutions actually serve employees. The Hub avoided this trap by focusing on community outcomes and not just design.

Qualitative feedback revealed unexpected benefits, especially after an equally unexpected boost in membership.

When a building flooded in 2019, the dean temporarily opened the Hub to displaced faculty who weren't yet members. André recalls the response:

People were coming up to me saying, 'I ran into colleagues I haven't seen in a decade. I love this space! Do you have monthly passes?'

That emergency access became the tipping point for voluntary adoption, revealing that the Hub was building social capital across a campus where clinical faculty typically operate in specialty-specific silos, and subconsciously felt isolated.

The success led to a second Hub in 2022, applying these lessons. Today, over 1,000 faculty members across multiple hubs actively choose to use the spaces rather than treating membership as a theoretical benefit.

Learnings for Employee Experience

The zero reversals statistic matters because it validates a specific approach to organizational change: design for choice rather than compliance.

Most workplace initiatives operate on an "we say so" model. Leadership decides and communicates a new policy, and expects adoption. Employee experience is a secondary concern addressed through change management programs and feedback surveys after implementation.

Nobody asks, "how will employees experience this?"

CU Anschutz inverted this model. Employee experience became the primary design constraint. If faculty didn’t choose to use the Hub, the initiative would fail—regardless of the savings or efficiency. This constraint forced the team to understand what faculty actually needed rather than what leadership assumed they required.

The voluntary framework also changed how employees engaged with the change. Faculty weren’t being told to give up an entitlement. They were being offered an alternative that might better serve how they actually work. The 1,000+ members suggest the alternative resonated.

This principle extends beyond the workspace to any situation where you need people to change behavior. Technology adoption. Process redesign. Organizational restructuring. The question becomes: If this were voluntary, would people choose it?

If the answer is no, you have two paths. Make it good enough that they would choose it. Or acknowledge you’re optimizing for compliance rather than experience—sometimes necessary for regulatory or safety reasons, but be honest about the tradeoff.

CU Anschutz chose the first path. The results validate the approach: 1,000+ members, zero reversals, faculty testimonials about reduced burnout and improved productivity.

That happened because designing for voluntary adoption forced them to build something genuinely better than what people had before. The real estate savings and space efficiency were byproducts of solving for employee experience first.

What To Do Monday

If you're leading or designing any organizational changes in 2026:

- Make one pilot voluntary to force quality through choice rather than compliance

- Invest in service alongside solution, as ongoing support matters more than launch quality

- Track what people actually do. Utilization and testimonials both matter, even if measured imperfectly

- Frame it as an experiment, so iteration signals learning rather than failure

The test: Would people choose this if they didn't have to?

If not, make it better before you scale it.